When Carroll James died at the age of 60 in March 1997, The New York Times opened its obituary by referring to him as “a Washington disk jockey whose promotion of the Beatles on his radio program helped make the group famous in the United States in the weeks before its first appearance on the Ed Sullivan Show in 1964.” The Washington Post was even more succinct in its farewell, referring to James as the DJ “who in 1963 was the first to play a Beatles record on the radio in the United States.”

That record was a little something titled “I Want to Hold Your Hand.”

The Times‘ obit insisted others came before him, noting that a Chicago station began playing ”Please Please Me” in February 1963, before Capitol Records planned on releasing the band’s music on this side of the Atlantic. But there was no denying that James’ advocacy — his enthusiastic fandom for four boys from Liverpool not yet beloved, revered or, for that matter, even very well known in the U.S. — laid the groundwork for his claim to fame as The Man Who Broke the Beatles.

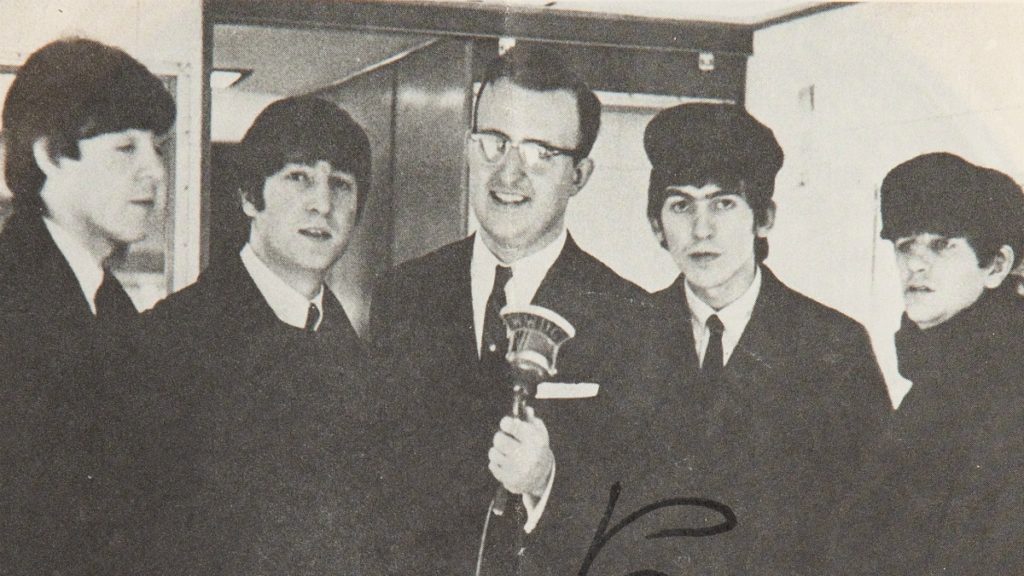

There is copious paperwork documenting his place in Beatles history contained in James’ personal archives that are part of Heritage Auctions’ massive Entertainment & Music Memorabilia event taking place August 8-9. The auction is filled with Beatles collectibles and keepsakes, none more personal than James’ binders filled with correspondence, fliers, photos, magazines and a recording of his Feb. 11, 1964, interview with the band at the Washington Coliseum — two nights after Ed Sullivan, and only moments before the Beatles’ first U.S. concert for which James served as emcee.

That recording, pressed on a seven-inch record whose sleeve bears a photo of James in the middle of the Fab Four, is signed by Paul McCartney.

To thumb through the collection is to trek back through time, to that strange moment before the Beatles were The Biggest Rock and Roll Band of All Time.

Contained in the archives, for instance, is a handwritten note from Louise Caldwell — George Harrison’s sister, who, in 1963, moved to the States and settled in the small town of Benton, Illinois. Louise famously trekked from one radio station to the next to scare up interest in her brother’s band only to find no takers.

In her missive to James, Caldwell writes of spending six months writing “countless letters” and driving “countless miles” to drop off Beatles records with disc jockeys — “and not one bright enthusiastic guy was to be found,” she laments. “I just wish that I could have found one DJ in the mid-west with your ‘drive.'” She thanked him for his persistence and wisdom, and wished him nothing but the success he so richly deserved.

Contained in the archives, too, is a letter James sent to Marsha Albert, who, in 1963, mailed James a request to hear the Beatles played on his station, WWDC. From The Post, the rest of the story:

“WWDC arranged for a British flight attendant to carry a copy over. After Mr. James played the record Dec. 17, the station was swamped with requests for the song. A tape made of Mr. James’s show was soon playing on stations across the country. As excitement over the group grew, Capitol Records released the record, six weeks earlier than planned.”

As a result, James caught the attention the Beatles’ press agent Brian Sommerville, as well as the group’s manager Brian Epstein. Missives from those famous gents are also in the archives, alongside fliers and pop charts and press releases documenting the station and James’ close-knit relationship with the Beatles upon their ascension to immortality.

There are letters, too, between Ed Sullivan’s reps and James about attending The Most Famous Television Show Ever; photos of the band; magazines documenting the Beatles’ rise to the top of the pops and beyond; and, astonishingly, even a flight pin from the British Airways flight attendant who brought the copy of “I Want to Hold Your Hand” to James.

“This type of insight is unprecedented,” says Heritage Auctions’ listing for this one-of-a-kind archive. History in the making, as it was being made.