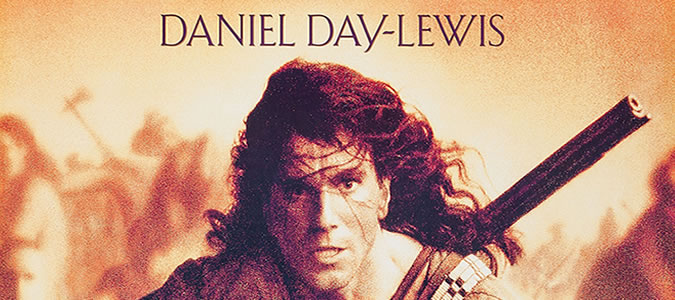

“Silk. Tight weave. Good for an extra twenty yards.” ~ Daniel Day-Lewis as “Hawkeye” in Last of the Mohicans as he hands Uncas a roll of fabric and begins loading his rifle.

The screenplay of the 1992 version of “Last of the Mohicans” took some generous liberties with Mr. Cooper’s story, but the prop department really outdid themselves in keeping things historically accurate.

A well-made muzzle-loading flint lock rifle is a thing of beauty unrivaled by any firearm created since the early 1800’s. Most people today think of all muzzle-loading rifles as “muskets”, but that is not correct.

A musket’s barrel is smooth on the inside like that of a modern shotgun. The musket was loaded by pouring loose gun powder down the barrel and dropping the spherical bullet down on top. Since the bullet was smaller than the interior diameter of the bore it was not stabilized when the gun was fired. The bullet rattled down the barrel and its flight path was somewhat random.

A rifle’s barrel has spiraled grooves (“rifling”) cut into the interior surface. These grooves cause the projectile to spin as it leaves the barrel. This gyroscopic force stabilizes the bullet making its flight more consistent. This consistency means the rifle will consistently shoot to the same point of impact.

The musket was the primary infantry weapon because it could be loaded and fired much faster than a rifle. The randomness of the bullet’s path meant it was only effective at ranges well under 100 yards. Wrapping the musket bullet in cloth or wet rawhide improved accuracy a bit, but the effective range was only about 75 yards on a man-sized target. Wrapping the bullet took extra time, so the military preference was for volume of fire over accuracy of fire. This lead military tacticians to favor large groups of men loading and firing as quickly as possible before charging in to settle the battle with the bayonet.

The rifle used a cloth “patch” to wrap the bullet. This patch kept the bullet centered in the barrel, and helped the rifling impart spin to the bullet. The thickness of the cloth, and the tightness of the weave reduce the amount of cloth that is torn and burned during the trip down the barrel. The better the cloth patch holds together, the better the bullet is stabilized, and greater the distance the rifleman can hit his target.

The two long arms pictured here are representative of the types of arms discussed in this article. The “Brown Bess” in variations was the standard musket used by the British military from 1722 to 1838.

The “Pennsylvania Rifle” pictured here is much more elaborately decorated than most frontier weapons of the times. They were usually plain rifles owned by private citizens, and brought from home when the men answered the call.

During the American Revolution, Colonial riflemen were able to hit British officers at ranges of 200-300 yards often changing the course of battles. All due to a little scrap of cloth.

Although I own and shoot a variety of replicas of antique arms, I am not fortunate enough to own any hand-made rifles. Working at Heritage allows me the opportunity to study history close up. Looking at the specimens of classic arms that come through our doors fills me with a sense of awe thinking of the frontier gunsmiths doing precision work to within a few thousandths of an inch using little more than hand tools. Some hoplophobic folks can’t see beauty in these things, but they are just as much a work of art as any Picasso.

By Michael Morgan