I’ve always loved history; always found the old stories and the old stuff just interesting.

As a consignment director here at Heritage’s Arms & Armor department I see a lot of old items and I often hear a lot of stories. Many of the stories are only word of mouth or from the family’s oral tradition. This can be a problem, but sometimes a verifiable story comes along.

Earlier this year a client shipped us his collection of guns and militaria put together over 40 years. He made a special point about a British Officer’s red plume, a Scottish basket-hilt sword with scabbard, a tin map tube, and a group medals. He said he thought they were from the Crimean War – not the one last month, but the one in 1854.

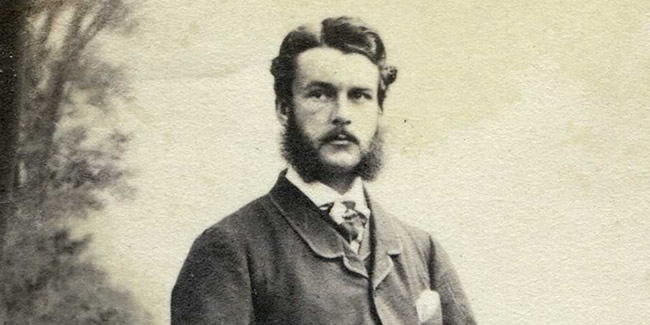

The consignor bought the group from the descendants of Major Henry Briscoe. His name is on the medals. You can look him up. I did. His service record reads: “Major H. W. Briscoe served in the Crimean campaign from Dec. 1854 to Aug. 1855, including the siege of Sebastopol, in the Trenches with the siege train, and at the bombardments of April 9th and June 6-7 (earning a medal with clasp, 5th Class of the Medjidie, and Turkish Medal). He served with the expedition to China in 1860, and was present at the capture of the Taku Forts, actions near Tangchow, and at the surrender of Peking (earning a medal with two clasps).” These are the exact same medals in the collection that was sent to Heritage. By now, I have decided that the collection is historically valuable and will stay together as one group lot in the auction. But the medals weren’t the only keepsakes sent to auction. Inside the envelope was a packet of letters – the icing on the cake.

The first page is an old hand-written note stating that these are Major Briscoe’s letters home from the war front.

They begin with “My dearest Mammy … I am off for Sebastopol to-morrow, we are to go in the Dauntless from Portsmouth … I am taking lots of Flannel things, as it is desperate cold out there … I am going out in Captain Oldfield’s company. I will be in the Siege train with the heavy guns, so will not be so much moved about as if I was in the Field Batteries. I fully intend as Gilly said, to extinguish myself, and come back with medals etc. one of these days.”

Perhaps “Gilly” misspoke and Henry is being cheeky. Well he did win medals and they have travelled half way round the world by now. Henry writes: “I got your welcome letters from home the other day. You can’t imagine what a comfort getting a line from anyone at home in this horrible place. Imagine yourself in the middle of Tybroughney bogs up to your knees in mud and then you have got it … but in about an hour I got quite accustomed to it and found myself sitting between two guns eating biscuit and now and then having a shot at the Russians.

“The enemy sent 3 shells into our battery but no one was hurt. Their riflemen are the chaps that kill our fellows. They are hid in pits about 400 yards in front of our batteries and peg at us when they get a chance.

“I amused myself by holding my cap on the top of a ramrod over the parapet and my eyes! Didn’t they let drive at it for a few minutes, but they soon found out it was only a trick, for they are rather sharp fellows. The line soldiers are worn off their legs, poor fellows … they are 12 hours on and 12 hours off duty and have to furnish work parties. The only thing I can compare them to is Irish beggarmen; that is just their appearance.”

At this point, I can’t resist sharing Henry’s tale with my sweet and patient wife. My wife is a nurse and she reminds me that Florence Nightingale and the Red Cross earned sterling reputations in the same region Henry was fighting. The Crimean War is also the first conflict to be documented by photographs.

Henry wrote almost each week for 6 months. He is a good writer and a fun read. He mentions going on leave with fellow officers and visiting ancient cultural sites in Greece.

He punctuates the dreariness of trench and siege warfare with details about horses he captured and raced, wild dogs (Sochi dogs?) they chased, and how important the care packages from home were to his health and morale. Later he mentions twice that his commanding officers have commended his unit and he wonders if he might receive a medal. He did.

One last remarkable statement from Henry was written just after sailing from England: “If I am only in time for the taking of Sebastopol, I may see some fun. I have got a Colts Revolver, and having bloody minded intentions towards the Russians, I have stuffed the wall of my Barrack room with Bullets practicing to get my hand in.”

In the gun collecting world, a little known story revolves around Sam Colt who by 1854 was marketing yet another popular pistol, the Colt 1851 Navy revolver. Colt, known as a tireless entrepreneur is said to have sold his pistols to both sides in that conflict. Our Henry has got one but what happened to it?!

This same consignor sent us a nice one with a serial number showing it was made in 1854. He doesn’t remember if it came from that Henry Briscoe family or not. Most Colt Model 1851 Navy revolvers owned by the Brits were marked slightly differently than ours. Is this Henry’s gun? Probably not.

So the Colt story is just that – a story. As intriguing as it may seem it is based on guess work and nothing more.

But Captain Briscoe’s letters are the stuff that history is made of.

By Clifford Chappell