It has been 38 years since Alex Haley published Roots in 1976. Michael Eric Dyson summed it up well in the 2006 introduction to the 30th Anniversary Edition of Roots: “Haley’s monumental achievement helped convince the nation that the black story is the American story.” If you know anything about American history, you know that was no small achievement.

I was far too young in 1976 to notice as the book sold almost 2 million copies within eight months of its publication and spent 22 weeks atop the New York Times best seller list (it was non-fiction). I also didn’t notice when the book earned Mr. Haley a Pulitzer Prize in 1977.

But I do remember bits of the Roots miniseries that aired on ABC in 1977—it formed some of my earliest television memories, along with Captain Kangaroo. In fact, most of the nation noticed the controversial and racially-charged miniseries (the final episode of the miniseries is the third highest-rated U.S. TV program), especially as it won a slew of awards and changed television and America. No doubt, Roots is an important work.

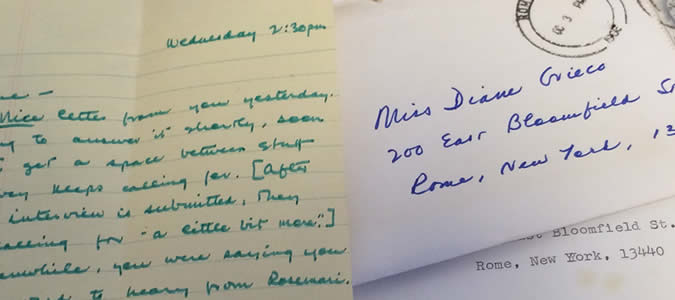

An early typed manuscript of chapter 2 of Roots has recently surfaced. It is twenty-four pages long with the heading, “2nd chapter. Rewrite” and is offered in Heritage Auctions’ upcoming Historical Manuscripts Signature Auction on April 3, 2014. Also offered is a fascinating collection of Alex Haley’s letters, all written to Diane Grieco, who served as his assistant from 1967-1969.

Those were productive years for the author as he began his magnum opus and continued working for Playboy magazine—conducting interviews, of course. Though Alex Haley died in 1992, Ms. Grieco has fond memories of working with the writer in New York. She graciously answered some of my questions about this collection and what it was like working with a man who knew he was writing a great book.

How did you meet Alex Haley?

When I was sixteen I was working in a small, family-type restaurant after school with several of my high-school girlfriends. Alex used to walk the streets of the city at night with his friend, George Sims, where they would toss about ideas and plans for the book. They would stop in the restaurant several times a week and, eventually, a friendship evolved between us.

In 1967 when you started working for him, Mr. Haley had already published his first book, The Autobiography of Malcolm X, and had just recently begun Roots. Can you give us an idea of what a typical day of working for him looked like then?

Usually by the time I would arrive at work there would be several tapes he had done during the night to be transcribed. Very often, I would see him for a few minutes, then he would be off to catch a train or a plane to somewhere. Many times I wouldn’t see him for several days. He was writing for Playboy at the same time he was researching and writing Roots and travelled a lot.

One of my favorite stories found in these letters is when Mr. Haley writes to you about being backstage at the Forrest Theatre in Philadelphia with Sammy Davis Jr. It’s a touching story because he relates how he brought your name up to the entertainer just before show time. When Mr. Davis took the stage, he had his band spontaneously change their opening number to “Diane,” surprising Mr. Haley! In that letter and so many others, he seems very thoughtful and generous. Is that how he was?

Immensely so! I remember the time he had to go to Boston to give a speech and asked me if I had ever been there. I hadn’t, so after clearing it with my parents he bought a ticket for me to go with him. He dropped me off at my hotel and left me to explore the city while he did his thing, then picked me up the next day and we flew home again. He was always doing things like that.

In some of these letters, Mr. Haley mentions working with celebrities. Throughout much of the 1960s, he conducted important interviews of people like Martin Luther King Jr. and Miles Davis for Playboy magazine. Did he have a favorite story that he told you about any of these interviews?

The story that has always stood out in my mind is the time he interviewed the head of the Ku Klux Klan for Playboy. I remember him telling me that the meeting place was secret and they had blindfolded him while he was being transported there. It was all done on their territory. I can only imagine being a black man, during that time in history meeting that particular person.

The letters in this collection show that Mr. Haley took an interest in your own budding writing career. In one letter he suggests that you “start preparing, developing yourself to become one day a professional writer.” In other letters, he gives you very specific advice on how to become a successful writer. Did your writing career ever get off the ground?

No, unfortunately, it never went any further. By the time I was 21 I fell in love, married and began having my babies, still though with writing on my mind. After sixteen years I became a single mother of three and needed a steady income, so I went back to secretarial work. When I retire, though, I’ve been thinking it would be fun to try it again just for fun.

Mr. Haley taught himself to write during his career in the U.S. Coast Guard. Do you think the lack of a mentor played a part in his wanting to mentor you as a young writer in the late 1960s?

With all the kind things he did for me I believe he enjoyed being my mentor, and yes, I also believe he did it because he had to go it alone for a long time. This all happened while the women’s movement was gearing up and he wanted me to see that all things were possible.

He got plenty of practice while he was in the Coast Guard by writing love letters to the wives and mothers of his buddies. Then he sold something to Reader’s Digest and he was off and running. I’m not saying it was easy for him from then on. He still had dues to pay before he became as famous as he did. It was many years before that happened.

Mr. Haley typed the manuscript on yellow paper. He also asked for more of this colored paper in a letter to you dated October 2, 1968. Was there something special about yellow paper?

He would do all the draft work on yellow paper and the finished work on regular white paper. After he got it pretty much the way he wanted it I would re-type it. This manuscript was the result of a research trip to Africa, I believe.

And green ink—there’s a lot of green ink on these pages!

Green was his favorite color and he always wrote with green felt tip pens. He was so poor when he started writing that I think it reminded him of money. I still have two of his pens.

One final question: do you think Mr. Haley knew in the late 1960s that he was writing such a ground breaking work?

He knew he was writing a great book.

By David Boozer